The poem moves from Dickinson to Galway Kinnell’s “St. ” Hayes opens the fifteenth sonnet with an assumption that I, at least, had yet to make, that Emily Dickinson “loved to masturbate.” This is a natural preoccupation the sonnet is traditionally concerned with eros and the psychology of desire.

It’s not even past.” Pound, too, whose Cantos show how all cultures and history can exist simultaneously in the poetic imagination, eliding the present: “What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage / Whose world, or mine or theirs or is it of none?” This isn’t mere poetry: Hayes has stood witness to our culture, learned from its history, and now brings the full force of his poetic intelligence to bear upon it.Īnd these truly are “American” sonnets subverting our Puritan heritage, Hayes “locks” his reader in close proximity to sex, so that these poems are “part prison / Part panic closet. There’s an element of Faulkner here: “The past is never dead. If the assassin is, in one sense, the reader, why then “past and future?” The poem’s last line helps to clarify: You assassinate my lovely legs and the muscular hook of my cock. Which is like the head of a turtle wearing my skull for a shell. You assassinate the smell of my breath, which is like In bushels of knotted roots, flowers and thorns until our body The bones managing the body’s business are cloaked You assassinate the sound of our bullshit & blissfulness. The tender bells of my nigga testicles are gone. The deep well of my nigga throat is assassinated.

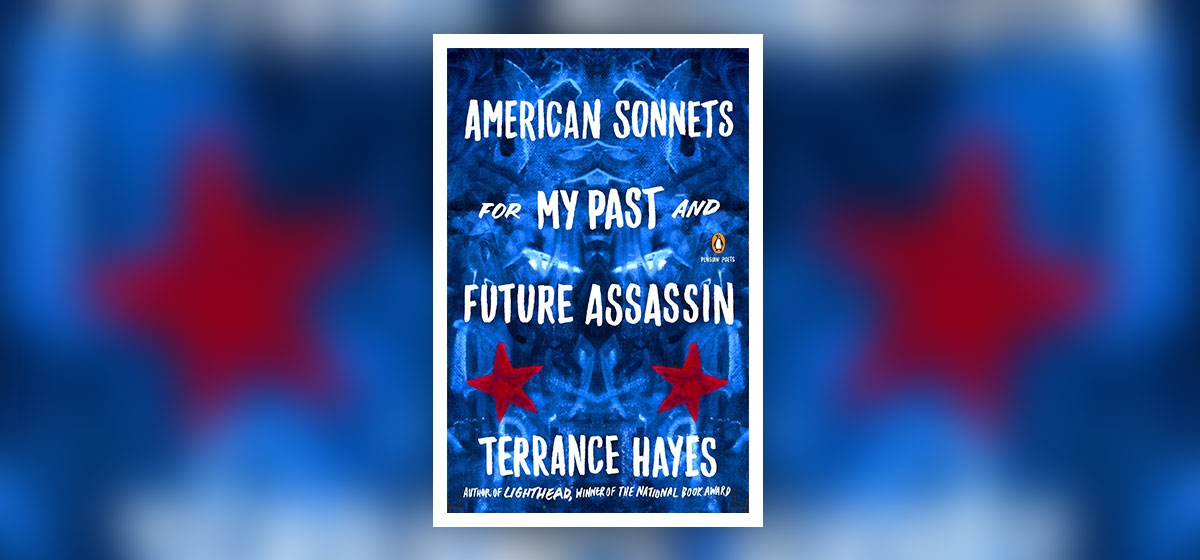

The earth of my nigga eyes are assassinated. Here is some of Hayes’s biting testimony, from the thirteenth in the sequence: The culture in which these “American Sonnets” exist could itself be the assassin. One of the abiding images in this collection of nearly eighty sonnets (all of which share the collection’s title) is that of the black body, so often consumed, caricatured, and recycled by the American artistic and literary idiom it’s helped to create. The last question might be easiest to answer. The title of Terrance Hayes’s new book, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, provokes a series of questions: Sonnets? Why? What makes them American? Past and future, but not present? How? And most pressingly, who is out to kill beloved poet Terrance Hayes?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)